Reaching 1 Million Users in 134 Days: The Breakthrough Strategy of an AI Entrepreneur

-

Tome is an AI-native storytelling platform that enables users to generate complete visual presentations in seconds with simple prompts. Similar generative AI presentation tools include Gamma and AI-enhanced document products like Notion.

Last week, Tome officially announced that its user base has surpassed 10 million, just six months after reaching 1 million in January. In February, the company secured a $43 million Series B funding round led by Lightspeed, with participation from Coatue, Greylock (Reid Hoffman serves on Tome's board), Stability AI CEO Emad Mostaque, and former Google CEO Eric Schmidt.

Keith Peiris is the co-founder and CEO of Tome. Prior to this, Keith served as a product lead at Instagram, Facebook, and Citizen.

This content is derived from Keith's online sharing, covering his transition from a product manager to an entrepreneur, the conception and development of early-stage products, as well as insights on growth, funding, commercialization, and AI. The full text is as follows:

- From Product Manager to Founder

- The Original Intent and Advantages of Founding Tome

- Iterating from Idea to MVP

- Vision? How It Guides Product Iteration

- What Are Tome's Competitive Advantages?

- The Journey to 1 Million Users in 134 Days

- Funding Insights and Commercialization Thoughts

- Team Size and Member Profiles

- Financial and Business Planning

- Will Tome Train Large Models?

- AI Enhances Rather Than Replaces

Keith Peiris

Many technical schools host robotics competitions annually. Initially, the competitions featured large robots capable of playing soccer—human-sized robots—then they became smaller, and smaller still. One year, they decided to hold a soccer match for a robot as thin as a human hair. At the time, I was studying nanophysics. It sounded incredible.

I've always wanted to build a robot, but I only learned things at this very tiny scale. I wanted to create a very small robot that could play soccer—one that could grab and move a tiny silicone disc. Through this process, I actually learned a lot about fundraising. When I wanted to start this project, the school refused to fund it, saying my grades weren't good enough and they didn't think I had a solid plan. So, I had to seek sponsorships from various companies that were trying to recruit computer science students from Waterloo. It took me several years to work on it.

In our first year, we performed terribly, but by the third year, we finally won the competition. Then, a year after I left, the team broke a series of records with these tiny soccer-playing robots. It was a very interesting startup lesson.

Grace Gong

So, how are nanorobots related to your successful products? You learned some cool lessons back then that helped kickstart your product career. You've also worked at big tech companies like Facebook, where even small changes you make can impact millions. Now that you're building something from scratch again, what early lessons have influenced you?

Keith Peiris

A few things. First, I was able to recruit very smart students to work on the robot. The first thing I learned was that when you work with truly talented people, you can't constrain them—you have to give them space to think, experiment, and play. For motivated and talented individuals, giving them autonomy and a goal can spark real creativity. But whenever I tried to micromanage or be too aggressive, the results were always worse. So, I learned some early management lessons from that.

Second, when building something extremely small—whether a robot or anything tiny—you can't handle too much complexity. A small mistake means you have to scrap everything and start over. My first version was overly complex. We couldn't even test the idea because we couldn't build it properly. That forced me to learn: start simple. When I joined Instagram, I realized the same principle applies to products—it's easy to come up with something complex, but making it simple requires a lot of refinement. This is a key lesson I carried from the physical world into digital products.

Lastly, like in startups, I feel a CEO's job is to face multiple rejections daily—whether from potential hires, investors, or unhappy customers—and find a way to keep going the next morning. In our case, we built 40 or 50 different versions, and only one truly succeeded. It was an accelerated lesson in the value of persistence.

Grace Gong

These are excellent lessons. When you mentioned facing rejection, I could hardly believe it. Just from the product perspective, it looks incredibly impressive, and considering the investors—you have Weig, Dan Rose (one of LinkedIn's founders), and Eric Schmidt—all top-tier operators turned investors. Out of curiosity, who are the people in your personal advisory team when it comes to career development?

Keith Peiris

In some ways, I've been very fortunate because I met many thoughtful people when I joined Facebook. Years later, they all left to create other things and become investors. That certainly helped. Regarding your question about my personal advisory team, I'm not sure I have a formal one. I have my fiancée, from whom I get advice on various matters.

Most of the time, I think there are many people with unique expertise in specific areas. Being able to connect with them for advice in specialized or creative fields is crucial. However, I find it challenging to find someone who excels in every domain. What's most important is that I have a group of people I turn to—when I have wild machine learning ideas, I consult them. I also have a network of CEOs I call for leadership decisions, and another group of product designers or investors who offer guidance.

I've developed a model where, when I need to learn something new—which is my current job—I always start by taking on the new role myself, then eventually hire or convince someone else to do it for me. I've found that I create this pattern: form my own perspective, discuss it with three to five people to refine it, then stop consulting others to develop new ideas and test them. So I'm constantly thinking about these micro-networks of expertise as I progress on this journey.

Grace Gong

In terms of skills, you've transitioned from engineer to product manager to CEO. Is there a skill you're continuously working to improve? It could be a technical skill like coding or a soft skill like sales.

Keith Peiris

One hard skill and one soft skill. For the hard skill, I'm currently catching up on machine learning. I feel I had a decent understanding of the possibilities in sorting, recommendations, and search from a decade ago. I'm really enjoying the progress made in recent years, but the moment I catch up, I'm behind again the next morning. So I'm constantly editing—this is my view of the world—and refining it has been very useful for me.

The other skill I'm working on is the ability to truly focus during presentations. If I look at my schedule today or this week, part of it involves finance, part involves hiring, marketing, product reviews, etc. I've found that if I carry thoughts from one meeting to the next, I can't perform effectively. It's a completely different game—almost like being a veterinarian: you see a dog, then a cat, a chicken, and a bird. So I'm trying to leave thoughts behind at the end of each meeting and focus entirely on the new one, without dwelling on the previous one.

Grace Gong

When you founded your company or incubated it at Greylock, what did you consider your personal strengths to be? And how did that translate into the company you were creating?

Keith Peiris

That's a great question, and I can think about it from a few different angles.

First, if you want to start your own company, one thing that was very clear to me is that I would have to pitch this company ten times a day, every day, for the rest of my life. When you consider that, you need to be deeply curious and fascinated by the problem space and the people you're serving to pitch it passionately. Because this is what you'll pour all your energy and thoughts into—a significant part of your adult life. If you're genuinely passionate and excited about the field you're in, then I think everything else becomes easier.

For me, I've always been deeply fascinated by communication. This has been the common thread in my work, even at Facebook. I first worked on search products, and I think of search as a form of communication—getting the machine to give you what you want. Then I worked on the Instagram camera or messaging on Instagram. I've always been fascinated by why people like talking to each other. Why are they afraid to talk to each other? What stops them from sharing their morning face? If you like someone, how do you break the ice?

So when I thought about different ideas, I knew I wanted to work on a communication company. And deep down, I knew I had some insights into communication because I'd worked on it before. But I also had this strong desire to work on the communication of ideas. That is, myself and everyone involved in camera products and social networks—we've made it very easy to share your face, what you did over the weekend, or what you ate. But if you want to share certain thoughts in your mind, we don't really have a great medium for that. You either have to record a podcast, make slides, or write a long document that no one will read.

I kept thinking: I want to reinvent how people share ideas to make them clear. I'm deeply fascinated by this problem and full of passion for it. And the people I want to serve—those who have ideas they want to share—they want their bosses to give them a chance to realize them, they want investors to fund them so they can bring their ideas to life. They want to write a story to attract people.

These sound like the people I want to serve for the long term. That's how Tome came about. Once I clarified what I wanted to work on for the next 10, 20, or 30 years, most of my thinking was: How do we turn this into a company?

I come from social networks, so my first thought was: Can we build a visual medium for ideas? I quickly realized this is a very difficult company to build, and it's an enterprise business model where not all incentives align. If you build an ad business, you just need people to keep creating because you want to serve ads to the audience. Or if you build something purely for consumers, you might not be able to build complex things that connect to different data sources or use a lot of computation.

Grace Gong

So how do you build a product that can eventually be commercialized?

Keith Peiris

First, I have a somewhat unconventional view when it comes to founding a company. The first person I want to bring on is a technical co-founder who can help me imagine and shape the product we want to build.

I believe that once we’ve defined the exact product we want to build, we can then hire a team to build it, rather than prematurely bringing someone on when we’re still unsure what to create.

I found my co-founder Henry through a mutual friend. In the first few months of Tome, we worked closely with Greylock to sketch out and envision what we wanted. When I say 'we,' I mean Henry—he was the one with the drawing and design skills. Both of us had worked in the mobile space for a while, so he designed Tome’s mobile prototype.

Imagine if you used Notion, Canva, or PowerPoint, or saw a tool primarily designed for mobile—it might seem unbelievable to many. So we showed this non-working prototype, just an idea, to friends who worked at these companies, and they all said it was really interesting.

'If you can figure out how to build it, we might pay for it,' they said. Then we started looking for our founding engineering team, who were incredibly excited to build the first version. We all shared the belief that we should start with something simple and let customers tell us what else they needed, ensuring we weren’t building anything unnecessary.

One scary thing in this space is accidentally spending five years rebuilding PowerPoint without ever achieving product-market fit. So our idea was to build a tiny thing we knew would work and then iterate. The first version of Tome only allowed you to place two tiles—a text tile and an image tile, for example.

We said, 'Try a page with just two tiles.' Of course, people didn’t get very far. Every team said, 'I need to put three things on a page,' and we started developing a system to allow more items. We built that system, got feedback, and then realized Tome needed themes and branding because that’s what companies required.

So we kept iterating, working with a small group until we created something many people wanted to use.

Grace Gong

Have you ever imagined that we would solve the world's biggest problems? At the very beginning, what was your vision for the future of work? How did it shape the way you iterated your product by following this vision?

Keith Peiris

Actually, I’ve been talking about what if we were building this company in 2030. I mean, we would leverage neural links to create something because, in a perfect world, you should be able to complete every transaction with full fidelity, as if connecting your brain directly to the person you want to tell a story to. But we’re not there yet.

So, what can we build with on-screen software before we reach that stage? He was really fascinated by the idea of a magical atmosphere—like in many RPG games, where there’s an ambiance with spells. We imagined something like opening a book, and holograms would jump out, telling stories and sharing everything. That’s the vision we wanted to achieve.

Then we asked ourselves: Google, Microsoft, and many others are already in this space, and the world has changed a lot—both culturally and technologically—since these tools were conceived. Is there enough room for startups to make a significant impact? The reason I say this is that traditional companies and new technologies usually don’t mix well, right?

Even though Microsoft contributed to cloud computing, you could argue they never truly transitioned Office to the cloud. Or when I was at Facebook, even though we knew mobile was important and tried to think about how to become a mobile-first company, we couldn’t build a mobile-native experience like Instagram or Snapchat.

We sat together and thought about how three things today are very different from 2000 or 2006 when Google Slides was released:

-

It’s almost obvious that mobile devices have become a fact of life, both at work and in daily life. We use them to watch stories, communicate via Slack, check Twitter, and read emails. I think if you’re building a 16:9 rectangular screen, it’s very hard to reimagine it for touch or mobile devices like iPads. And we believe there’s a long road ahead because many people, especially younger generations or those in developing countries, no longer own laptops. That’s a key point.

-

We hold a belief that in the modern world, the best stories are multimodal. By this, I mean there are modalities in media, such as video, images, and text, but in the internet age, you should be able to reference different data sources from various places. Even when I worked at Facebook or Instagram, my presentations were screenshots from different web services—screenshots of data, customer feedback, and design files. We believed we should build a tool that connects different data sources because the best stories will reference many different sources and extract various objects from them. Traditional companies, it seems, haven't thought about this; they focus on, say, drawing a graphical canvas. So we thought, 'Oh, this seems very fundamental to how people work and think.'

-

We believe that if you read many presentations—I reviewed about 20,000 before starting—you'll notice that many stories follow familiar patterns, just expressed differently. Many product review presentations follow very similar structures, and this turns out to be very true. The way you fill in the details is the unique part. I like to joke that every Pixar movie follows a similar narrative structure, yet each is unique in its own way. Back then, there was a technology that could connect things, allowing me to read every story and presentation in the world and then link them to build a structure for your story. That would be transformative, right? As a thought partner, it would be insanely transformative. At that time, GPT was something like that. We weren’t sure if it would get better in two or five years—it was a timeframe—but we knew it would become a significant part of the company, given advancements in mobile devices, different modalities, web services, and large language models. However, for a big company to change its approach would be very difficult.

We thought, if we start from scratch and save their time by considering all this, could we build something so good that we’d get a head start of several years and move as fast as possible? That was the main idea. Of course, you can’t predict exactly when all these things will materialize, but so far, much of it has been correct.

Grace Gong: I think your initial product was truly amazing. Tome reached 1 million users in just 134 days after launch, making it the fastest productivity tool to hit that milestone, surpassing Dropbox, Slack, and Zoom. I’m curious—how did such rapid growth happen? How did you adapt so quickly? You mentioned 40–50 versions before the first product launch. How did people adopt and use the product so quickly at the beginning?

Keith Peiris: One thing I wish I could tell myself two years ago is that the internet is a highly efficient distribution channel. If you build something that’s genuinely ten times better than what people are currently using, it will spread rapidly on its own—through Twitter, Reddit, Discord, and TikTok.

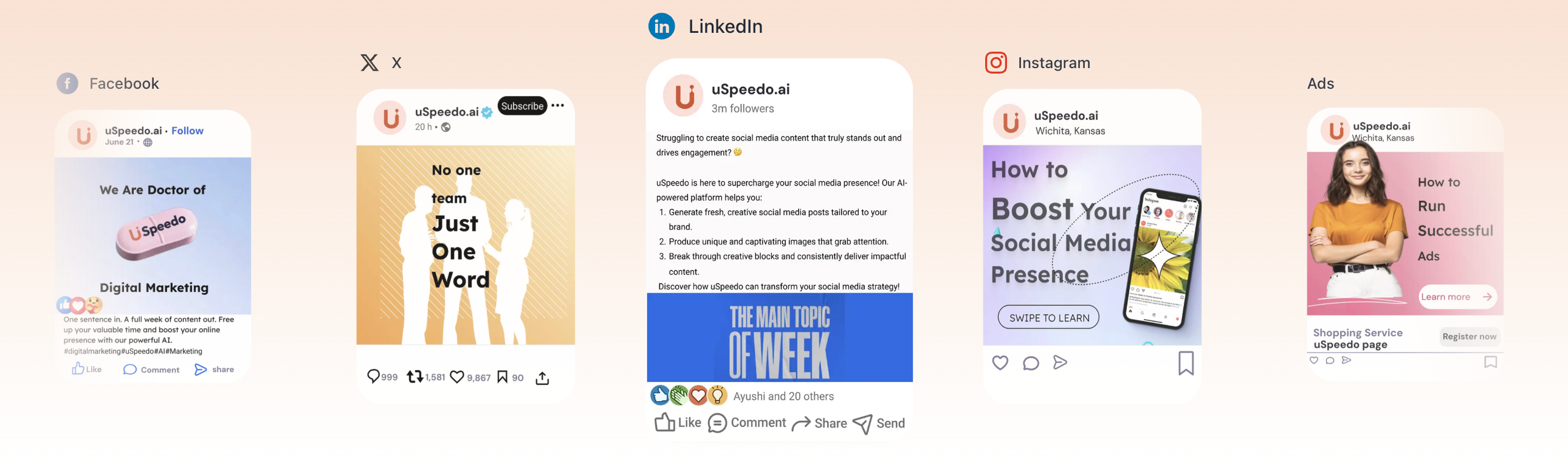

I believe that as a founder, your primary goal is to build something truly better. We've done what a good go-to-market team should do—whenever we launch a new feature, we always email existing customers first and create a short video to post on social media.

When we first launched the initial version of Tome, we thought it was decent enough to release. After posting the video, it quickly went viral. Both Henry and I posted it a week before Christmas, and it kept getting shared repeatedly. Soon, celebrities on TikTok discovered it, and customers started flooding in.

It became a snowball effect. During the holidays, our service hit bottlenecks as usage exceeded OpenAI's access limits—a clear sign things were taking off. We realized our job now was to persevere and shape our brand.

Now we reach out to celebrities for collaborations to help launch our next product. The craziest development in recent months has been the complete shift in our user base—from just a few thousand teams (like product, engineering, and design teams who were highly proficient with our tools) to a diverse range of users. One of our biggest internal challenges is prioritizing next steps because we receive varied requests from authors, students, CTOs, founders, and product managers. We're navigating this tough prioritization path.

Grace Gong:

Initially, you didn't approach it from a product perspective—people don't want to create from scratch. They prefer working from a foundation, perhaps with an existing format as guidance rather than starting from zero.You're one of the first AI-first companies, unlike large corporations that started long ago and later added AI to their teams. I'm curious—and I'm sure investors ask this too—what's your competitive advantage? For instance, when Microsoft or others suddenly integrate AI (especially Microsoft, which invested in OpenAI), they likely have more advantages in AI integration. How do you address this? And what advantages do AI-first companies have over these giants?

Keith Peiris:

Regarding being AI-first or native AI, I see it as envisioning how to design and conceptualize products with capabilities, constraints, and limitations in mind.One obvious aspect is that when you ask a large language model or image-generation model to create something, it's a highly iterative process—almost like collaborating with a person. There's a back-and-forth dialogue for editing and refining until the final output differs significantly from the initial instruction.

When using design tools, I place a rectangle here and an arrow there—I'm very directive. So when building AI-native products, much of our thinking revolves around creating something that feels conversational, though not necessarily within a chat window. It's about generating content for you, then providing tools to drag, shape, and refine it while incorporating feedback to train the model. Ultimately, we arrive at a different outcome.

We learn from interactions—whether you prefer direct, logical writing styles or generating images with cyberpunk aesthetics—and start delivering more of what you want. Reflecting on this, I realize how challenging it would be to integrate such features into a product that's been around for 20 years.

A good analogy is Tesla: designing an electric vehicle requires placing batteries at a low center of gravity, reengineering transmissions for torque, and redesigning dashboards since driving time decreases compared to traditional cars. Similarly, Tome feels fundamentally different from legacy products—like retrofitting an electric motor onto a combustion engine versus building from the ground up. Now we're beginning to realize these benefits through enterprise pilots.

A frequent request from interested parties is the ability to build atop our large language model while maintaining their own data layer—uploading company repositories (documents, charts, data) and integrating these facts into GPT-4's framework. This third aspect proves exceptionally difficult without full commitment. Currently, we're weaving corporate assets (like internal wikis) into LLMs to create outputs that mirror a company's unique voice.

While large corporations could theoretically do this themselves, treating it as a side project presents significant challenges.

Grace Gong: Your recent $43M funding at a $300M valuation attracted prominent investors. What was your funding journey like before this? Also, what's the business model—$10/user/month with enterprise plans? How do you prioritize monetization?

Keith Peiris: Early-stage funding remains nascent. After two years operating, we've learned we can't convince investors of what they don't inherently believe. For us, aligning with backers who share our vision of technology and market scale has been crucial.

Frankly speaking, we need to find them as soon as possible and minimize interactions with those who hold different views. For instance, we deliberately adopted a highly consumer-centric go-to-market strategy, meaning we believe this gives us the best chance to build a lasting company.

For users, it will always be free, and it can grow organically through people sharing Tome on the internet. We are confident that if you bring it to work, you will eventually be willing to pay for it. This bottom-up, consumer-driven approach is the best way to build an engineering company because it allows us to compete against the massive sales teams of public companies.

We’ve gone through multiple funding rounds and found that insightful consumer-focused (toC) investors understand this. They talk about network effects, virality, engagement retention, and how we envision driving the product's growth. For them, this is a very important yet straightforward approach because you can highlight lightweight, mobile-friendly formats and the abundance of such content. As a result, we’ve connected with many who share our beliefs, and for them, this is quickly and clearly evident.

Another key insight is that we sought investors who actually use our product, not those merely trying to spot an opportunity. This was an interesting discovery. One challenge for companies like ours is the need to build horizontally while also considering vertical go-to-market strategies. For example, who is the text editor designed for? Who is the chart system meant for? These tools can serve a wide range of users.

Thus, you need to build horizontally for many users while remaining confident about later entering the enterprise market vertically. We’ve found that not everyone in Silicon Valley believes in this approach—it ultimately comes down to faith.

We will soon introduce paid plans, though a free version will always remain available. This quarter, we don’t want to charge students; we want them to use the product freely and unleash their creativity. One reason we’re introducing pricing is that we have exciting developments on the horizon. A common question from customers is about obtaining unlimited computing power—they don’t want to worry about quotas when performing different tasks. They simply want computing resources available when needed, such as when preparing critical presentations. I feel the same way—when working, I don’t want to think about quotas. This is one of the reasons we’re moving forward with this change.

Another reason is that it helps us identify who is seriously using the tool. Some users engage daily, generating multiple Tome documents, but this differs from those willing to pay monthly. This will help us focus on the right user personas and roadmap priorities. Internally, we’ve discussed our ambition to grow into an enterprise company—but at the right pace.

Focusing too early on enterprises and teams risks losing the magic of being a startup—the opportunity to build a product people love that can scale. It could also lead to over-prioritizing enterprise-specific features. So, while we’re exploring what an enterprise version might look like and running experiments, we’ll never forget that, at our core, we are a consumer-first company.

Grace Gong

I’m curious—when you first started and were raising funds, was Tome already what it is today? Or did it lack the functionality it has now? What was the AI industry like back then? You began about two years ago, and now AI is a hot topic.

Keith Peiris

When it comes to fundraising, I believe you must be completely honest about what you have and what you need to build next. In the earliest stages, we had excellent prototypes. Henrik is an exceptional product person who created comprehensive blueprints in Figma, built various prototypes demonstrating potential features, and showcased presentations. Meanwhile, I conducted extensive customer research through Survey Monkey surveys, phone interviews with potential clients, and Zoom recordings to understand their perspectives on PowerPoint and requirements for new tools. We presented this information to show we knew exactly what we were dealing with.

Honestly, we just needed to build it—and this approach resonated with many investors, proving effective. Regarding AI, it's interesting—I recall a quote from Stripe's CEO: 'It's hard to predict what will happen in 1-3 years, but you can more accurately forecast the next decade.' I strongly relate to this. While I don't know what next year's economy will look like, I have expectations for the next 10 years.

When designing Tome, we knew large language models and machine translation would be crucial components, though we weren't sure whether this would materialize in 2022, 2024, 2026, or 2029. Based on this, we decided to form a small team to build what we knew was necessary while staying attuned to developments. We monitored progress, stability, and key milestones until the direction became clear—which it did last year.

Grace Gong

What does your talent structure look like? For example, what's the ratio of engineers to designers? How many are in sales or business roles? This is important for business professionals like us. What was your thought process when building the team? And how do you allocate budgets—is it bottom-up ('we need to achieve $X in sales in 2023, so we'll form 10 teams') or top-down?

Keith Peiris

The answer is always a mix. We created a simple Google Sheet to determine how many people we could hire, then adjusted daily based on needs.

Our philosophy: When starting a company, try to hire one exceptional person each month, then someone even better the next month. Eventually, hiring becomes harder because you've built an outstanding team—this acts as a control mechanism.

As a startup, you're convincing people to take a risk on you, so you're often limited by who you can find rather than what you can pay. We've always maintained constraints and preferred small teams (currently 71 people according to LinkedIn)—you can always do more when necessary.

We need to be very precise about the next 1-3 hires, and we'll continuously reassess because as a founder, you receive a lot of new information in the early stages. Your user base might completely change next week, all your customers could be different next week, and you might encounter infrastructure issues next week—so many things are changing. I don't think overly rigid long-term planning is beneficial. What I focus on is whether I'm making the best decision for the next hire—that's what matters most.

Grace Gong

You've raised a significant amount of funding—what are your plans for utilizing it? For example, building a team focused on cutting-edge technology? Or what are your intentions?

Keith Peiris

We're a technology and product company, so we're heavily investing in advancing machine learning, as well as growing our design, product, and engineering teams.

As you know, this has always been our core. I believe this is a place where people come to build something they're proud of. What you create on Tome should be the best work of your career compared to previous companies—so this will be a major investment.

That said, we're transitioning into a company with more users than a few months ago, handling payment issues, and exploring the enterprise market. So, we're building a very strong sales team to refine all aspects, but our goal is to stay as small and lean as possible for as long as we can.

I think everyone shares the same background and mindset—everyone owns a part of the company. Given how we structure compensation, we're all highly focused and truly aligned with the mission. For me, this is one of the most exciting parts of building a company at this scale. We'll try to maintain this scale for as long as possible.

Grace Gong

I've heard many companies are developing using technologies like GPT-4 provided by OpenAI, such as GPT-4 on AWS. Why is everyone building on this? How difficult is it to train your own model? Suppose I have a unique need—you mentioned Tome can help leverage your unique writing style to create content. For example, I don't want every presentation from the internet—I only want something like YC documents. If I've raised $100M, how can I add this layer to my Tome? Is this already possible, or are you working on it? How does the technical composition work?

Keith Peiris

First, we consider using these foundational models as a platform. I think it's more akin to the comparison between AWS, Google, and Azure—it's more of an oligopoly than a monopoly. I believe there will be three to five major players, all rapidly evolving, with many companies excelling and fine-tuning for slightly different applications.

Our perspective is to build the best experience for customers. We've designed our system to seamlessly replace models to ensure optimal performance. Even if we currently use one model for image generation, newer and superior models are emerging from different vendors. We never want to fall behind in using the best models for our clients because, in this evolving space, our ability to iterate and adapt is crucial for survival.

Our current focus is on how to obtain data sources for you and your company—data that involves facts you'll use repeatedly. This is paramount. If you work at a bank, we want you to utilize your bank's research and facts. If you're at a Web3 company, we want you to discuss your technology, not some fabricated narrative from a language model.

Regarding style, it's interesting—we often debate whether Tome should sound like you or simply sound good. Currently, the priority is making Tome sound compelling, persuasive, and authentic. Personalization in style might come later.

For your next question about training—how to train only the right presentations, not the wrong ones? It's a great question. We're exploring this. If you go into OpenAI's Playground, you can extract content as part of the context window, perform short-term training on it, and then generate outputs based on that content.

One cool aspect of GPT is its immediate access to a large context window, up to 25 pages. This provides a background for localized training on specific topics. We're working on some projects that I think will be very compelling in the coming months.

Grace Gong: What will the future of work look like for you? Currently, a hot topic is the divided opinion on AI—some are excited about the future, while others fear AI will take their jobs. What's your take? How will it impact future work?

Keith Peiris: At Tome, we don't believe AI will completely replace human jobs. We firmly believe AI is a tool for human augmentation—helping us achieve our dreams better, faster, and more efficiently. This excites us because no matter how much you train a machine, it can't create a presentation without human input. A presentation embodies your vision, your imagination, and the company you want to build.

The best assistant can only provide you with some successful examples and a universally effective structure, but shaping it into something of your own is what you, as a human, need to do. That's where the excitement lies.

When I think about the future of work, the reason we focus on storytelling is that I believe storytelling is a fundamental building block of productivity. When I persuade you to work with me by telling a compelling story, sometimes it involves facts, sometimes visuals—this is how I collaborate with you. Therefore, I see storytelling as a prerequisite for coordinating work. We need coordination to tackle big and small challenges together.

We know Tome is a company of its time. If we can help anyone tell a captivating story, we believe the best ideas will prevail. We think society will collaborate on these ideas. When I reflect on misinformation on the internet, you know, we talk about filter bubbles—that's part of it, where we only hear from those who share our views. But I think the other side of the issue is that we have a great platform for exchanging and discussing complex ideas. Hopefully, Tome can be a step in the right direction, helping people discuss intricate issues with more nuance.